NORRISTOWN >> Police are called with increasing frequency for complaints about a homeless man with mental health issues. A boy who lives in a household familiar to authorities for domestic issues has started skipping school and breaking curfew. An unemployed mother of three with no previous criminal record is arrested for drug possession.

These are examples of bad situations that many law enforcement officials agree often get worse.

But what if that was not necessarily the case? What if police and other public health and safety professionals collaborated on these cases using a comprehensive strategy that enabled them to mitigate risk factors and intervene to address small infractions before they snowball into larger ones, effectively reducing and preventing crime?

That is the goal of the Whole of Government concept, presented at the 2015 International Conference on Proven Collaborative Strategies for Improved Community Wellness and Safety recently held at the King of Prussia Radisson and conducted by the Penn State Justice and Safety Institute (PSJSI). The concept, which has a proven track record of success in Canada, is being implemented by a small number of forward-thinking law enforcement agencies in the U.S., including Norristown.

Joseph DeStefano, conference chairman and client/business development manager for PSJSI, is a former police officer who has spent 40 years in various aspects of law enforcement, including corrections, juvenile justice and public safety. The Penn State grad, who has worked with the university for the past 14 years, explained that the crime-reduction strategy is based on communication between public entities, derived from a risk-driven, rather than an incident-driven, perspective.

“When I was a police officer, you got a call, you went to it. That was incident-driven,” DeStefano said. “This is pulling people from government units together to identify the people at high risk and getting the specific units to collaborate on what would best meet those needs and risks, so it’s revolutionary.”

DeStefano’s exposure to the Whole of Government concept came, in part, from Norman Taylor, the senior advisor to the Saskatchewan and Ontario Deputy Minister for Justice. Seven years ago, Taylor, an independent consulting advisor specializing in policing and community safety, was commissioned to perform a “future of police” study in Saskatchewan, which at that time was leading Canadian provinces in violent crime. After researching the problem and studying possible solutions, Taylor and his team came to a seemingly obvious yet obfuscated conclusion.

“What I identified, together with the police department and other stakeholders in the process, is that there wasn’t a policing problem. They had a problem with marginal citizens with multiple risk factors that just kept coming into the system,” Taylor said. “We find this to be common with just about every jurisdiction we know ― that it’s a very small percentage of people that create most of the demand on not only policing, but the other services as well.”

Taking a cue from a similar program that produced positive outcomes in Glasgow, Scotland, Taylor wrote a report in 2010 calling for a “whole of government approach,” concentrating on a holistic response to risk factors, rather than addressing the issue as strictly a crime problem for law enforcement to deal with independently.

Soon after the study’s completion, a proof-of-concept model was implemented in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and officials were astounded by the results ― so much so that the program has expanded to 13 jurisdictions throughout the province and to nearly 30 communities across Canada.

“A number of studies have been done,” Taylor said. “Among the most immediate numbers that caught people’s attention was a 39 percent reduction in violent crimes in Prince Albert. That occurred within the first year and has been sustained.

“Literally 100 child apprehension files didn’t have to get opened because we had other solutions available. We had 900 missing persons cases, usually teenagers in runaway, walk away situations. We’re down to under 200 a year.”

Taylor also cited reductions in mental health crises and youth disorder, along with improvements in school attendance.

“Just as strong has been the feedback in terms of agencies,” he continued. “The efficiency of the model, the reduction in the demands on their time. So agencies that have gotten involved just keep wanting to go further with us.”

The Whole of Government law enforcement program consists of two main components: the hub, where police representatives meet with social services, mental health providers, educators, addiction specialists, employment counselors and other officials to discuss specific cases; and the core, where agencies that can offer the most relevant risk-abatement services collaborate on solutions and form a plan of action.

The process, which culminates in some type of outreach or intervention, is carefully evaluated through a four-tiered filtering process that insures the privacy of case subjects by only informing core agencies of pertinent identifying information.

At the conference, a procedural overview of the hub and core concepts was presented in the plenary sessions, with breakout sessions conducted by presenters with Whole of Government expertise in four main areas: evidence based and research driven practices; obtaining needed collaboration resources and funding; meeting critical challenges of corrections, re-entry, mental health and information sharing; and best practices for marginalized populations.

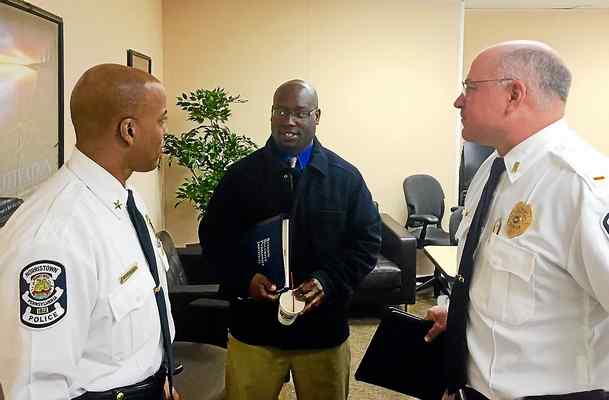

Norristown police Chief Mark Talbot Sr., who studied organizational leadership at Penn State and has done some leadership teaching for PSJSI, became familiar with the Whole of Government concept while researching collaborative crime reduction strategies. He recognized the potential benefits and attended the conference with several officers from the department. Contingents from the Lewistown, State College, and Abington police departments were also in attendance, joining law enforcement officials from Baltimore and Miami who expressed interest in a pilot program. The NPD is one of the first police departments in the nation to implement the Whole of Government model.

“One of the things that was highlighted at the conference was the fact that we are incarcerating people in this country at a rate which far exceeds that of any other industrialized country in the world, and that really doesn’t make any sense,” said Talbot a week after the conference at a Norristown hub meeting, consisting of about a dozen social service providers and other public safety stakeholders. “If we have so many social services and service agencies that are positioned to deal with crime and quality of life issues, why would we be doing things that way? Why would that be our reality?”

Talbot said he believes that part of the solution is identifying problems “upstream,” well before they get to the police.

“What we’ve done in the NPD is really moving past some of the heavy enforcement tactics to make Norristown safe, to look at who else is out there doing good things in the community and doing them in a very purposeful way,” he said. “I’m understanding better at this point in my career than I ever have, that you all may see problems long before we do, or you may recognize it long before we do. And if we have the discussion ahead of time, we’ll be ahead of the game.”

Talbot stressed the importance of those at the table being open to change and willing to share information in order to make the collaborative approach yield its intended results.

“If you’re going to really wake people up and shift from the traditional way of doing business to a model where you are embracing your responsibility to save people’s lives, you really have to have a passionate conversation and not allow people to do and think the same things that they always thought,” Talbot said.

Jessica Fenchel, the director of the Adult Mobile Crisis Support Program at Access Services, has worked in the mental health field for nearly 20 years, in both the juvenile and adult systems. Finchel has been in discussions with Talbot about crime and quality of life issues for more than a year and was one of the earliest proponents of the Whole of Government concept.

Talbot credited her with recognizing and emphasizing the need for specialization as it pertains to managing cases appropriately.

“I hope it ― the Whole of Government model ― will help us avert unsafe scenarios and crisis scenarios for individuals and families,” said Fenchel. “This particular model could really support developing the connections in the community that it seems are really necessary to avert some of the crime that he (Talbot) is seeing and some of the crises that I’m seeing.”

“I think the hub is great,” said Hakim Jones, truancy abatement specialist for the Norristown Area School District.

“Statistics of truancy point to jail,” Jones said. “They point to dropping out of school. They point to struggling financially, lack of employment. And also being a victim of a crime is big with truancy. Children who aren’t in school are at higher risk of being victims of crime.”

Jones said the new approach to law enforcement will work because it puts police and social service on the same page while providing families “with a network of resources available to help better their situations.”

Talbot couldn’t agree more.

“If you listen to this (approach to community safety) and don’t realize about that fast” ― here he snapped his fingers ― “that it’s the right way to do things, you’re probably off track because this is what we should have been doing all along. ”

Taken from The Times Herald on August 8th, 2016